When it comes to waste, reducing the amount sent to landfill where it causes numerous problems seems like a simple goal to rally around—but as with most things, the devil is the detail. Zero waste means avoiding waste at all stages of a product’s lifecycle; from the original design and the extraction of its raw materials, right through to end of life. And yet the plethora of terms and processes that populate the field has the potential to cause confusion among the public and provide a smokescreen for businesses to conceal poor environmental practices.

In essence, this is how greenwashing occurs—a practice that can be mitigated with clear and distinct labelling that prizes transparency over misleading claims. Two such terms that are currently in popular use and that would benefit from distinction are ‘biodegradable’ and ‘compostable’. There is an overlap between the two terms but while compostable materials are always biodegradable, the reverse is not always true. So, what is the difference?

What Does Biodegradable Mean?

It’s easy to see where the confusion comes from when both biodegradable and compostable denote a material or product which can be broken down by nature’s own hand. Biodegradable is a broad, catch-all term for something that can be broken down into its core elements by one or another biological process.

The time it takes to do so can vary greatly depending on the component materials and the input variables of oxygen, water, light and temperature. It is worth noting that most landfills are not optimized for biodegradation as they often lack the light and oxygen required to hasten the process adequately. As a result, the term biodegradable is ripe for misunderstanding and corporate greenwashing.

What Does Compostable Mean?

If something is compostable it means that it can be subjected to the natural decomposition of organic matter into compost; a nutrient rich fertilizer. Compost benefits the environment directly by infusing the ground with nutrients derived from the incoming organic waste (your coffee grounds, food waste, garden cuttings etc.), and indirectly by diverting greenhouse gas-emitting matter away from landfill, where it would otherwise end up.

As with biodegradation, composting needs specific, usually human-induced conditions to work effectively. Aeration is the most common method of composting on both an industrial and consumer scale. Here, green matter (e.g. food waste) and brown matter (e.g. leaves) are combined with oxygen to aid decomposition. In commercial composting, higher temperatures are created to speed up the process.

Composting can also take place at home in a process called anaerobic composting, for example in a bokashi bin. The common denominator in composting, and the distinguishing factor from biodegradable products, is that composting not only eliminates waste from landfill but produces an environmentally valuable output—compost.

Bioplastics – Compostable vs Biodegradable

Source: rts.com

The rise of biodegradable and compostable plastics (bioplastics) has created another layer of confusion around the rush for more environmentally friendly products. As companies seek to satisfy rising consumer demands for sustainable materials, there is a latent concern over the true viability and even danger of such materials.

The distinction to make about bioplastic items (we see it in cutlery, straws, and containers, etc.) labeled ‘compostable’ or ‘biodegradable’ is that they require the conditions of a commercial facility to break down properly. This is a major caveat compared to the convenience and symbiosis of backyard composting.

The corollary is that much of it will simply end up in landfill instead of an industrial composting facility. Even though these products may still break down faster than conventional plastics, touting them as a lasting solution is a fallacy. More so when we consider that bioplastics are made out of fossil raw materials as well as bio-based materials, and so often pack a punch in terms of lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions. Clearly, bioplastics are not a silver bullet.

Which is Better – Compostable or Biodegradable?

Which should you seek out between compostable vs biodegradable products? Well, it should be clear by now that comparing these two terms head-to-head isn’t particularly helpful, except to dispel their conflation in the public consciousness.

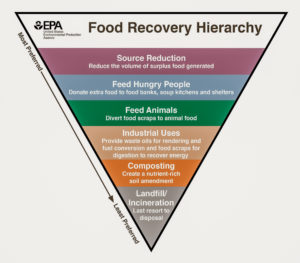

Source: epa.gov

By their very nature, inorganic materials (e.g. plastics) are not compostable and although certain products can be cleverly reimagined with compostable raw materials (e.g. mushroom packaging), many things can’t and shouldn’t be. In this sense, organic, compostable products should be considered in a separate category from biodegradable products. The latter term spans too different and broad a range of applications to be comparable.

Composting is certainly higher on the zero-waste hierarchy than sending biodegradable waste to landfill to break down. But there are caveats to compostable items too. Just because something can be composted doesn’t mean it will be. And even though composting in its purest form is rightly seen as a sustainable process, we have a duty to reduce composting too where possible.

There are four preferable steps on the EPA’s (Environmental Protection Agency) Food Recovery Hierarchy. For example, we should first look to reduce the source of waste food and redirect it to those in need before composting it.

Arguably, the bottom line in comparing these distinct terms is that while compostable materials can achieve something like a closed-loop system for organic waste, biodegradable materials are almost certain to have a negative impact on the environment during the process of decomposition.

Marketing Biodegradable vs Compostable Products

Because a biodegradable or compostable product is seen as a step up from its predecessor, consumers have been encouraged to view it as a perfect solution. We see this in everyday items such as biodegradable or compostable plastic bags or baby wipes. Marketing around these products, particularly on the labeling, sidesteps the fact that they may only be compostable or biodegradable at industrial facilities.

They also eschew the glaring reality that these are still innately wasteful products; we should turn to reusable bags and wipes. Furthermore, such products usually come wrapped in single use plastic packaging. As consumers we have to take care to check the details on the packaging to find out whether you can compost a product at home or not. Studies show that consumers find it hard to discern the difference between third-party certifications and businesses’ own green proclamations.

Zero Waste — The Future of Materials

The zero-waste movement aspires to create a closed loop system, or circular economy, where products and their manufacturing processes are reimagined so as to negate waste altogether. Organic, compostable materials are by their very nature predisposed to this circularity, whereas the distinct category of non-organic, biodegradable materials is less so.

In this sense, we are comparing apples to oranges. The rise of compostable and biodegradable bioplastics has contributed to the popularity of the two terms among brands, and although bioplastics are an improvement on traditional counterparts, we should remember that they require industrial facilities to compost or biodegrade. We must also be mindful that corporations are not above paying lip service to sustainability by slapping the words biodegradable or compostable on a product without third-party accreditation.

Visit the zero-waste blog for more tips and guides on finding genuine zero-waste products and introducing zero-waste strategies to your everyday life.